K-Nearest Neighbors

- 1. KNN algorithm

- 2. Decision Boundary

- 3. Curse of Dimensionality

- 4. Python Implementation: Classification

1. KNN algorithm

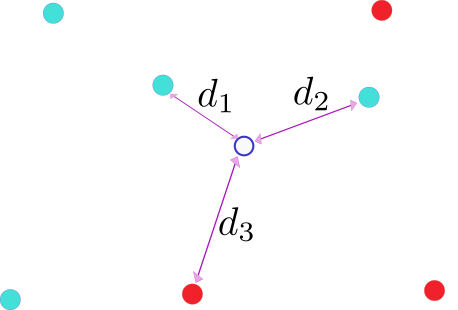

The nearest-neighbors algorithm considers the $K$ nearest neighbors of a datapoint $x$ to predict its label. In the figure below, we have represented a binary classification problem (colors red and green for classes 0,1 respectively) with datapoints living in a 2-dimensional feature space.

The algorithm consists in attributing the majority class amongts the $K$-nearest neighbors. In the example above we consider the 3 nearest neighbors using euclidean distances. Mathematically the predictor $\hat{y}$ is given by

\[\hat{y}(x)=\text{argmax}_{0,1}\{n_0(x),n_1(x): x\in D_K(x)\}\]where $D_K(x)$ is the set of $K$-nearest neighbors and $n_{0,1}(x)$ are the number of neighbors in $D_K$ with class $0,1$ respectively. The ratio $n_{0,1}/K$ are the corresponding probabilities. For a multiclass problem the predictor follows a similar logic except that we choose the majority class for which $n_i(x)$ is the maximum, with $i$ denoting the possible classes.

A probabilistic approach to nearest neighbors is as follows. We consider the distribution

\[p(x|c)=\frac{1}{N_c\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}^{D/2}}\sum_{n\in\text{class c},n=1}^{n=N_c}e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_n\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}\]with $N_c$ the number of points with class $c$ which have coordinates $\mu_c$, and $x$ lives in $D$ dimensions. The probabilities $p(c)$ are determined from the observed frequencies, that is,

\[p(c=0)=\frac{N_0}{N_0+N_1},\;p(c=1)=\frac{N_1}{N_0+N_1}\]The ratio of the likelihoods is then

\[\frac{p(c=1|x)}{p(c=0|x)}=\frac{p(x|c=1)p(c=1)}{p(x|c=0)p(c=0)}=\frac{\sum_{n=1}^{n=N_1}e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_n\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}{\sum_{n=1}^{n=N_0}e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_n\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}\]Take $d(x)$ as the largest distance within the set of $K$-nearest neighbors of the datapoint $x$. If the variance $\sigma$ is of order $\sim d$ then the exponentials with arguments $|x-\mu|^2>d^2$ can be neglected while for $|x-\mu|^2<d^2$ the exponential becomes of order one, and so we approximate

\[\frac{\sum_{n=1}^{n=N_1}e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_n\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}{\sum_{n=1}^{n=N_0}e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_n\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}\simeq \frac{\sum_{i\in D_K^1(x)} e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_i\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}{\sum_{j\in D_K^0(x)} e^{-\frac{\|x-\mu_j\|^2}{2\sigma^2}}}\sim\frac{\#i}{\#j}\]where $D^{0,1}_K(x)$ are the nearest neihgbors of $x$ with classes $0,1$ respectively, and $#i+#j=K$. In theory this would reproduce the K-nearest neighbors predictor. However, this would require that for each $x$ the threshold $d$ is approximately constant, which may not happen in practice. The algorithm is however exact as $\sigma\rightarrow 0$ for which only the nearest neighbor is picked.

In regression we calculate instead the average of $K$-nearest neighbor targets. That is,

\[\hat{y}(x)=\frac{1}{K}\sum_{i\in D_K(x)}y_i\]Consider different datasets whereby the positions of the datapoints $x$ do not change but the target $y$ is drawn randomly as $f+\epsilon$ where $f$ is the true target and $\epsilon$ is a normally distributed random variable with mean zero and variance $\sigma^2$. The bias is thus calculated as

\[\text{Bias}(x)=f(x)-\text{E}[\hat{f}(x)]=f(x)-\frac{1}{K}\sum_{i\in D_K(x)}f(x_i)\]For $K$ small the nearest neighbors will have targets $f(x_i)$ that are approximately equal to $f(x)$, by continuity. As such, the bias is small for small values of $K$. However, as $K$ grows we are probing datapoints that are farther and farther away and thus more distinct from $f(x)$, which in general will make the bias increase.

On the other hand, the variance at a point $x$, that is,

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f})|_x=\text{E}[(\hat{f}(x)-\text{E}[\hat{f}(x)])^2]\]becomes equal to

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f})=\frac{\sigma^2}{K}\]Therefore, for large values of $K$ the variance decreases, while it is larger for smaller values of $K$.

2. Decision Boundary

In the picture below, we draw the decision boundary for a $K=1$ nearest neighbor. For any point located inside the polygon (hard lines), the nearest neighbor is $P_1$, and so the predicted target is $f(P_1)$ in that region.

To construct the decision boundary, we draw lines joining each point to $P_1$, and for each of these, we draw the corresponding bisector. For example, consider the points $P_1$ and $P_2$. For any point along the bisector of $\overline{P_1P_2}$, the distance to $P_1$ is the same as the distance to $P_2$. Therefore, the polygon formed by drawing all the bisectors bounds a region where the nearest point is $P_1$.

For $K>1$, we have to proceed slightly differently. First, we construct the $K=1$ decision boundary- this determines the nearest neighbor. Call this point $N_1$, the first neighbor. Second, we pretend that the point $N_1$ is not part of the dataset and proceed as in the first step. The corresponding nearest neighbor $N_2$ is then the second nearest neighbor while including $N_1$. We proceed iteratively after $K$ steps. The decision boundary is then determined by joining the $K=1$ polygons of each $N_1,N_2,\ldots N_K$.

3. Curse of Dimensionality

In this section, we discuss the K-nearest neighbors algorithm in higher dimensions. Consider a sphere of radius $r=1$ in $d$ dimensions. We want to calculate the probability of finding the nearest neighbor at a distance $r<=1$ from centre. This probability density is calculated as follows. Let $p_r$ be the probability of finding a point at a distance $r$ and $p_{>r}$ the probability of finding a point at a distance $>r$. Then the probability that we want can be written as

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split}&Np_r p_{>r}^{N-1}+\frac{1}{2}N(N-1)p_r^2p_{>r}^{N-2}+\ldots\\ &=(p_r+p_{>r})^N-p_{>r}^N\end{split}\end{equation*}\]which is the probability of finding at least one point at $r$ and none for $< r$. The probability $p_r$ is infinitesimally small, since

\[p_r=r^{d-1}dr\]while $p_{>r}=(1-r^d)$. Hence, we can expand the expression above and determine the probability density

\[\frac{dP(r)}{dr}=N r^{d-1}(1-r^{d})^{N-1}\]Take $d\gg1$. The probability density has a maximum at

\[r^*=\frac{1}{N^{1/d}}\]For the K-nearest neighbors algorithm to perform well, there should exist at each point a sufficiently large number of neighbors at distances $\epsilon\ll 1$, so one can use the continuity property of a smooth function. Therefore if we insist that $r^*=\epsilon\ll 1$, this implies that $N$ must be exponentially large as a function of $d$. In other words, for higher dimensions, the probability of finding a neighbor at distance $\epsilon$ is smaller because there is more “space” available. To compensate for that, we need an exponentially larger number of datapoints.

4. Python Implementation: Classification

Define KNN class with fit and call methods. The fit method memorizes the training data and the call method retrieves the predictor.

class KNN:

def __init__(self,k):

self.k=k

self.x=None

self.y=None

self.classes=None

def fit(self,x,y):

self.x=x

classes=sorted(set(y))

self.classes={a:b for b,a in enumerate(classes)}

self.y=np.zeros((y.shape[0],len(classes)))

for i,a in enumerate(y):

j=self.classes[a]

self.y[i][j]=1

def __call__(self,x):

if len(x.shape)==1:

t=x.reshape(1,-1)

else:

t=x

y_pred=np.zeros((t.shape[0],1))

for i,z in enumerate(t):

z=z.reshape(1,-1)

norm=self.x-z

norm=np.linalg.norm(norm,axis=1)

args=np.argpartition(norm,self.k)[:self.k]

ypred=self.y[args].mean(0)

ypred=ypred.argmax()

y_pred[i]=ypred

return y_pred

As an example, load Iris dataset and also the built-in SKlearn K-nearest neighbors algorithm.

from sklearn.datasets import load_iris

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

iris=load_iris()

features=iris['data']

target=iris['target']

#train & test split

indices=np.arange(0,features.shape[0])

np.random.shuffle(indices)

l=int(0.2*features.shape[0])

xtrain=features[indices][:-l]

xtest=features[indices][-l:]

ytrain=target[indices][:-l]

ytest=target[indices][-l:]

knn=KNN(30) #the class above

Kneighbor=KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=30) #the SKlearn class

knn.fit(xtrain,ytrain)

accuracy_score(ytest,knn(xtest))

Kneighbor.fit(xtrain,ytrain)

accuracy_score(ytest,Kneighbor.predict(xtest))

Retrieving exactly the same accuracy.