Stochastic Gradient Descent

1. SGD

Gradient descent is an algorithm for solving optimization problems. It uses the gradients of the function we want to optimize to search for a solution. The concept is straightforward. Suppose we want to minimize a loss function. We start by choosing a random point in the loss function surface. Then we make a step proportional to the function’s gradient at that point but in the opposite direction. This guarantees if the step is sufficiently small that the new point has a smaller loss value. We continue this process until the gradient is zero or smaller than a predefined threshold.

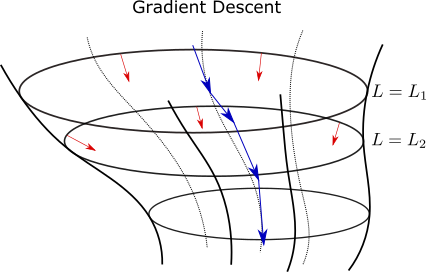

The loss is usually a multivariate function in a high dimensional space, that is, $L=L(x)$ with $x\in\mathbb{R}^d$. The gradient descent ensures that we always take steps in a direction orthogonal to constant loss value surfaces. That is, consider the region that has a loss value $L=L_1$. A small step $dx$ along this surface does not change the loss value. Therefore we must have

\(\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_1}dx_1+\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_2}dx_2+\ldots+\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_d}dx_d=\frac{\partial L}{\partial x}\cdot dx=0\) and so the gradient vector $\partial L /\partial x$ is an orthogonal vector to the surface $L=L_1$. In other words, a gradient step moves the parameter away from surfaces of constant loss.

In practice, we perform the update \(w_t=w_{t-1}-\eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{t-1}}\) where $w$ is the parameter to be learned and $\eta$ is the learning rate. Usually, we need to adapt the learning rate during the descent. A large learning rate may lead to non-convergent results. On the other hand, a small learning rate will make the convergence very slow.

One of the most important shortcomings of the gradient descent is that it may get stuck in a local minimum. To add to this, calculating the gradient at every step may be computationally very expensive. For example, in neural networks, the computational cost is at least of order $\mathcal{O}(Nm)$, where $N$ is the number of datapoints and $m$ the number of parameters. For large neural networks with millions of parameters, calculating the gradient at each step is infeasible. To solve these issues, instead of calculating the loss overall all datapoints, we can consider small batches at each step. We calculate the contribution to the gradient from the smaller batch

\(\frac{\partial L^{B}}{\partial w}=\sum_{i\in\text{Batch}}\frac{\partial L_i}{\partial w}\)

where $L_i$ is the loss contribution from a single datapoint, and use this to update the parameters iteratively.

In stochastic gradient descent, we update the parameters using small-batch gradient descent. We run through all small-batches to guarantee that we learn all the data. Suppose we have a sequence of non-overlapping and randomly chosen small batches ${B_0,B_1,\ldots,B_n}$ each of size $b$. Then at each step in the gradient descent, we update the parameters using the corresponding batch, that is,

\[w_t=w_{t-1}-\eta \frac{\partial L^{B_{t-1}}}{\partial w_{t-1}}\]Once we run over all batches, if the parameters $w_t$ do not change considerably, the total distance traveled in parameter space is proportional to the gradient calculated on the full dataset. That is,

\[\sum_{t=0}^T \Delta w_t=-\eta \sum_{t=0}^T \frac{\partial L^{B_{t-1}}}{\partial w_{t-1}}\simeq -\eta\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_{T}}\]If the batches have size one, then this is a Monte-Carlo estimation of the unbiased gradient descent $\sum_i \frac{\partial L_i}{\partial w}D(x_i)$, where $D(x_i)$ is the actual distribution, and hence the name stochastic descent. Even if the descent takes us to a local minimum, the batch-gradient may not be zero, and we will avoid being stuck there.

2. Variants

- Momentum

The stochastic gradient descent can drift the learning over directions in feature space that are not relevant. This happens because at each step the new gradient step does not remember past movements. To compensate for this one may add a “velocity” component $v_t$, that is,

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &v_{t}=\gamma v_{t-1}-\eta \frac{\partial L^{B_{t-1}}}{\partial w_{t-1}}\\ &w_t=w_{t-1}+v_{t} \end{split}\end{equation*}\]where $\gamma$ is the velocity parameter and $v_{0}=0$. Since $\gamma<1$, movements in the far past become less and less important. However, recent movements can contribute significantly. In essence, we are calculating an exponentially decaying average of the past gradients. This average eliminates frequent oscillations and reinforces relevant directions of the descent.

- Nesterov accelerated gradient (NAG)

The NAG learning is very similar to the momentum update, except that it introduces corrections to the gradient. So instead of calculating the gradient at $w_{t-1}$, it is calculated at $w_{t-1}+\gamma v_{t-1}$. That is,

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &v_{t}=\gamma v_{t-1}-\eta \frac{\partial L^{B_{t-1}}}{\partial w_{t-1}}(w_{t-1}+\gamma v_{t-1})\\ &w_t=w_{t-1}+v_{t} \end{split}\end{equation*}\]The shift by $\gamma v_{t-1}$ brings corrections to gradient.

- AdaGrad

Adagrad or adaptive gradient introduces a learning rate that varies through the descent. The algorithm consists in the sequence

\[w_{t,i}=w_{t-1,i}-\frac{\eta}{\sqrt{G_{t-1,ii}}}g_{t-1,i}\]where $g_{t,i}$ are the gradients for the parameter component $w_{t-1,i}$, and \(G_{t-1,ii}=\sum_{\tau=0}^tg^2_{\tau,i}\) is the sum of all the squared gradients up to time $t$. The solution is actually more complicated but also computationally more expensive. The matrix $G_{t,ii}$ is replaced by the full matrix \(G_t=\sum_{\tau=0}^tg_{\tau}g_{\tau}^T\), where $g_t$ is now the gradient vector. This choice guarantees optimal bounds on the regret function. During the stochastic descent new data is introduced at each step in order to estimate the update of the parameters. The regret function calculates the difference between the acumulated loss at time $t$ and the actual minimum of the loss known at time $t$. Bounding the regret guarantees that the update algorithm takes us close to the desired solution.

- AdaDelta

The Adagrad algorithm makes the learning rate very small after some time. This happens because the matrix $G_{t,ii}$ accumulates all the past gradients, and thus becomes increasingly larger. Instead, we can calculate a weighted sum over the squared gradients which prevents contributions in the far past to be relevant. That is,

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &E(g)_t=\gamma E(g)_{t-1}+(1-\gamma)g_t^2\\ &w_{t,i}=w_{t-1,i}-\frac{\eta}{\sqrt{ E(g)_{t-1,ii} }}g_{t-1,i} \end{split}\end{equation*}\]A similar algorithm which goes by the name RMSprop has been developed independently around the same time as the Adadelta.

- Adam

The Adam or adaptive momentum estimation, adds further improvements in the Adadelta algorithm. The update algorithm introduces a momentum component in addition to the squared gradients,

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &v_t=\gamma_1 v_{t-1}+(1-\gamma_1) g_t\\ &E(g)_t=\gamma_2 E(g)_{t-1}+(1-\gamma_2)g_t^2 \end{split}\end{equation*}\]But it also introduces bias corrections. That is, after time $t$, the components above have the expression

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &v_t=(1-\gamma_1)\sum_{\tau=0}^{t}\gamma_1^{t-\tau}g_{\tau}\\ &E(g)_t=(1-\gamma_2)\sum_{\tau=0}^{t}\gamma_2^{t-\tau}g^2_{\tau} \end{split}\end{equation*}\]Assuming that $g_{\tau}$ is drawn i.i.d according to some distribution, we take the expectation values

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &\mathbb{E}(v_t)=\mathbb{E}(g_{t})(1-\gamma_1)\sum_{\tau=1}^{t}\gamma_1^{t-\tau}=\mathbb{E}(g_{t})(1-\gamma_1^t)\\ &\mathbb{E}(E(g)_t) = \mathbb{E}(g^2_{t}) (1-\gamma_2)\sum_{\tau=1}^{t}\gamma_2^{t-\tau}=\mathbb{E}(g^2_{t}) (1-\gamma_2^t) \end{split}\end{equation*}\]So to guarantee that we have \(\mathbb{E}(v_t)=\mathbb{E}(g_{t})\) and \(\mathbb{E}(E(g)_t) = \mathbb{E}(g^2_{t})\) we rescale $v_t$ and $E(g)_t$ by $(1-\gamma_1^t)$ and $(1-\gamma_2^t)$ respectively. The update becomes

\[\begin{equation*}\begin{split} &\hat{v}_t=\frac{v_t}{1-\gamma_1^t}\\ &\hat{E}(g)_t=\frac{E(g)_t}{(1-\gamma_2^t)}\\ &w_{t,i}=w_{t-1,i}-\frac{\eta}{\sqrt{ \hat{E}(g)_{t-1,ii} }}\hat{v}_{t-1,i} \end{split}\end{equation*}\]Note that Adam reduces to Adadelta when $\gamma_1=0$.

References

[1] Adaptive Subgradient Methods for Online Learning and Stochastic Optimization, J. Duchi, E. Hazan, Y. Singer, (2011)

[2] Adam: a method for stochastic optimization, D. Kingma, J. L. Ba, (2015)

[3] Lecture 6a: Overview of mini-batch gradient descent, G. Hinton, (CS lectures)

[4] Introduction to Online Convex Optimization, E. Hazan

[5] An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms, S. Ruder, arXiv:1609.04747